By Steve Wampler

After receiving his newly minted Ph.D. in electrical engineering from Northwestern University in 1995, LLNL’s John Chang set out on a four-month, around-the-world journey.

It was an adventuresome trek that changed his life and still, some 27 years later, deeply impacts him.

As he travelled, Chang visited about a dozen different countries and sought to immerse himself with the people and cultures of some of the world’s most mountainous regions, including the Himalayas in Asia and the Alps in Europe.

The medical needs and poverty he saw in some areas as he travelled led him over time to devote literally thousands of hours and much of his life to a new avocation – working on search-and-rescue missions.

“A major motivation for me to volunteer for search-and-rescue was being compelled to want to help people in need,” said Chang, 56, an electrical engineer in the Lab’s Computational Engineering Division.

“This desire grew out of my travels because when I came to villages in the mountains, people needed medical help and I was not prepared to be able to help them.

“When I went on trails in remote areas, the trails weren’t built for recreational hiking. The trails were only delicate links between villages. They were carved into the mountains, narrow, steep and dangerous in some places.”

After he returned from his around-the-world trip and started a postdoctoral appointment in biomedicine as a cancer researcher at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, Chang received his introduction to search-and-rescue work.

Nestled in the Upper Valley area of the Connecticut River with the oldest engineering school in the United States, the Ivy League college and its medical school decided to form a search-and-rescue organization to help the community, just as Chang was beginning his postdoc research.

“With the Appalachian Trail running through the heart of the Dartmouth campus, the area’s rural nature and the extreme volatility of the weather of sudden ice storms and blizzards, people thought it would be a good idea to form a search-and-rescue team,” Chang recalled.

After arriving on campus, Chang came across a flyer seeking volunteers to join a search-and-rescue team. He signed up for the team and then took an emergency medical technician (EMT) course at Dartmouth.

During his four years at Dartmouth, Chang participated in 20 to 40 different missions to find or rescue missing people, with the search-and-rescue team finding the missing people alive about two-thirds of the time.

In 1997, an elderly gentleman diagnosed with dementia walked down a long pathway on his property to retrieve his mail and disappeared in a rural area of New Hampshire.

With severe winter conditions of snow on the ground and temperatures in the upper 20s, the missing man had been lost for 24 hours and was suffering from hypothermia.

“Our team found him,” Chang said. “He was less than a mile from his house, on the ground, accompanied by his small dog, Snoopy, who apparently stayed by his owner’s side all through the time he was lost.”

Chang was the EMT who treated him.

“It was a tremendous thing to find him alive. His family’s reaction and the reaction of other families to having their loved ones found alive is often typical: they’re elated, thankful and exhausted.”

But, as Chang notes, every search-and-rescue mission is unique: “They might have similar attributes or commonalities but you can’t predict the outcome.”

One of Chang’s first missions as a member of the Upper Valley Wilderness Response Team was to assist in the body recovery of an Appalachian Trail hiker who had become stranded and died in New Hampshire’s White Mountains during the first winter storm of 1995-96.

“That was my first body recovery. We had a team of about 20 people that used a litter to carry out the hiker and the conditions were horrible,” he said. “The trail was narrow, steep and composed of ice and loose dirt. One of our great concerns was that the rescuers didn’t become victims themselves.

“The recovery operation for the hiker made a deep impression on me. I recognized the importance of going into hazardous environments to recover the remains of those who are lost.

“We always hope for the best – finding the missing person alive. When we don’t, the thing that brings us solace is knowing that we brought a person home to their family and have given them closure.”

As he thinks back on his time with the Dartmouth search-and-rescue team, Chang says the volunteer work gave him the privilege and opportunity to explore the richness of the New England region.

After his four years at Dartmouth and before he joined LLNL in 1999, he book-ended his postdoctoral appointment with a second four-month, around-the-world adventure.

This time, he journeyed to other mountainous geographical regions formed by what is often called the “Ring of Fire” of the Pacific Ocean, including Patagonia in the Andes Mountains between Chile and Argentina. He also visited the South Pacific, taking in Easter Island, French Polynesia and Tahiti; and included Australia and New Zealand before transitioning to California.

“Within a few months to a year of arriving at LLNL in April 1999, I decided I wanted to continue doing search-and-rescue work, with an emphasis on technical mountain rescue work,” he said.

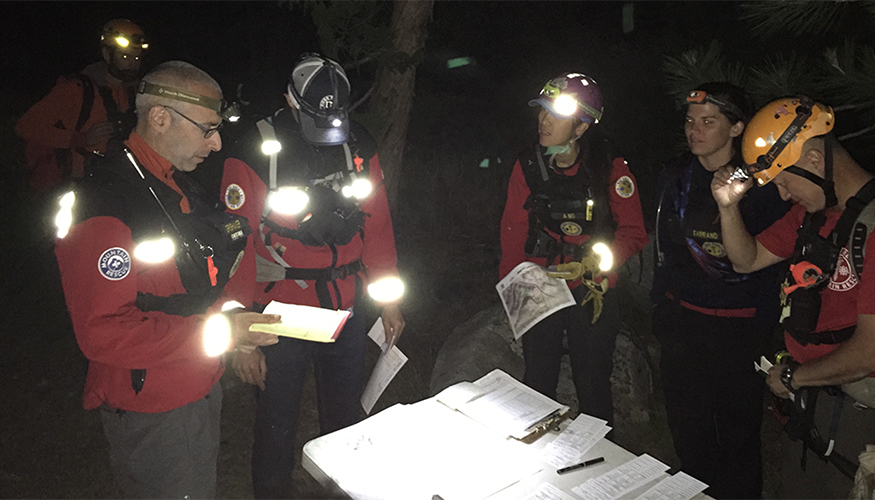

As a result, Chang joined the then-two-dozen members of the Bay Area Mountain Rescue Unit (BAMRU), a search-and-rescue team affiliated with the San Mateo Sheriff’s Office of Emergency Services. BAMRU places a heavy emphasis on developing the skills to respond to missions across California in the most challenging and extreme conditions and terrains.

Today, Chang is the only LLNL employee who works as a BAMRU member. But that wasn’t always the case.

BAMRU’s roots date back 56 years to the summer of 1966 when an LLNL (then known as Lawrence Radiation Laboratory) employee was reported by his family as overdue from a solo hike along the walls of Yosemite’s Tenaya Canyon.

When park rangers didn’t find the employee, Quin Charles Frizzell, dozens of Lab coworkers joined the hunt. Climbers and others found no trace of Frizzell after a week, so the search was abandoned. (Frizzell’s remains were found about six years later in 1972).

The returned searchers formed a volunteer mountain rescue unit called the Alameda County Mountain Rescue Service (the forerunner to BAMRU) that was composed almost entirely of LLNL employees, including the unit’s first president, George Bloom.

Today, BAMRU can be deployed for up to 72 hours for people in harm’s way in all terrain, all weather and all seasons. Operations include searches for missing or lost individuals in the high Sierra, communities affected by wildfires, along coastal cliffs and in other wilderness environments. The team is comprised of rock climbers, mountaineers, backpackers and backcountry skiers.

“Many times, when we start searching for a missing person it is easy to believe it’s a lost cause,” Chang said. “That’s what makes it so special and rewarding when we find someone who could have perished.”

One apparent “lost cause” that turned into a rousing success happened for BAMRU and other search-and-rescue organizations in 2012 when a hunter in Mendocino County became separated from his hunting companion and was lost for 19 days.

Upwards of 200 searchers hunted for nearly three weeks for 72-year-old San Francisco resident Gene Penaflor, seeking without luck to find him in a linear distance area of 15 miles by 15 miles, or 275 square miles.

As search-and-rescue organizations were phoning Penaflor’s next-of-kin to inform them that they were suspending the search, the hunter was found alive and well outside the search area by another group of hunters.

“He knew what he was doing,” Chang said. “He applied survival skills, sheltered himself under fallen trees, drank from nearby springs of water and ate lizards.”

Chang performed the initial medical assessment on Penaflor and called him “incredibly coherent given the circumstances.”

In October 2004, the first winter storm of the season hit California hard. Seven climbers were stranded on El Capitan in Yosemite. BAMRU and numerous other search-and-rescue groups lent support to the Yosemite search-and-rescue team of the National Park Service.

“It was very memorable because the whole state was in trouble. With the bad weather, the rescue teams couldn’t fly helicopters, hike, climb or gain frontal access to El Capitan,” said Chang, who was a member of the support team that ferried equipment to the rescuers.

To get to the top of the peak, the rescuers hiked 11 miles around the back of the mountain and then were lowered down to reach the stranded climbers. Two of the climbers died and five were rescued.

Since he joined BAMRU in about 2000, Chang estimates that the unit has participated in about 35 search-and-rescue missions per year, or about 770 missions, over the past 22 years. The missing individuals have been found alive in about two-thirds of the cases.

The Lab employee himself has gone on about 250 of the BAMRU’s search-and-rescue missions over more than two decades. In addition, he has served on the leadership team for 18 years, including two stints as the unit leader, from 2004-2006 and from 2011-2021, devoting about 40-60 hours per month to the team’s efforts as unit leader. He also has served in multiple leadership positions for the Mountain Rescue Association (MRA), including as the chairman for the California region of the MRA as a national-level officer.

Starting with the EMT course he took as a postdoc at Dartmouth, he has expanded his search-and-rescue skill set through the years, including wilderness medicine, backcountry skiing, rock climbing, mountaineering and man-tracking, which is the ability to track footprints.

Chang and the approximately 80 other current BAMRU members engage in monthly search-and-rescue training, including sending rope climbers over cliffs in Yosemite National Park to practice rescues; and conducting mountain climbing at Mt. Shasta, Mt. Whitney and along the cliffs of the Pacific coastline in the Bay Area. As part of the MRA, Chang also has participated in training and exercises across North America from the deserts of Arizona to the Rocky Mountains, the Pacific Northwest and Alaska.

Over the past dozen years, the BAMRU team has responded to two major California disasters – the 2010 Pacific Gas & Electric Co. gas pipeline explosion in San Bruno and the approximately 153,000-acre conflagration of 2018 known as the Camp Fire in the area surrounding the city of Paradise in Butte County.

On Sept. 9, 2010, after working for the day at LLNL, Chang was driving on the San Mateo Bridge to the San Mateo Sheriff’s Office headquarters in Redwood City for a BAMRU meeting when he spotted a large plume of smoke rising near San Francisco International Airport.

Upon arriving at his unit’s meeting, Chang learned that the sheriff’s office had activated the BAMRU unit because of a major explosion in San Bruno that turned out to be the PG&E gas pipeline explosion.

That night, Chang, about 20 other BAMRU members and the San Mateo Office of Emergency Services helped law enforcement with crowd control until about 3 a.m.

For the next two days, the BAMRU members, including Chang, searched the Crestmoor residential neighborhood for survivors and remains.

“It is hard to describe and imagine the effects on a neighborhood of such a massive burning explosion,” he said. “The precision of the devastating blow torch effect left one resident’s home half-charred to the foundation next to a kitchen table still with dishes and table settings seemingly only slightly disturbed.”

Within about four days of the start of the 17-day Camp Fire in Butte County, which caused 85 civilian fatalities and burned more than 18,000 structures, BAMRU was activated to provide assistance.

About 10-15 different BAMRU search-and-rescue team members assisted with the Camp Fire on a daily basis. “When there’s a fire, the firefighters are fully occupied with fire suppression, but search-and-rescue teams are needed afterward to find and account for missing people,” he said.

After each day’s mission, the emergency responders would return to the base camp to recuperate, eat their meals, debrief the day’s events and even do their laundry.

“One of the most heart-warming and heart-wrenching experiences was meeting a local Paradise resident who was a teacher and who was helping run the laundry service for emergency responders even though her own home had been destroyed by fire just days earlier,” Chang said.

“The landscape and level of devastation in the burned area was shocking. When I was in Paradise, the whole town was empty except for first responders and search-and-rescue team members.”

In Chang’s view, the bonds that are created among search-and-rescue team members through the experiences of shared rescues and life-and-death situations result in enriching and enduring lifelong ties.

“The camaraderie that is built into the search-and-rescue community is foundationally based on the core values of serving those in need. That, in combination, with independent-minded people, brings out the best of our human nature even as we all continue to try to moderate our individual shortcomings,” he said.

Some of his work at LLNL dovetails with his avocational search-and-rescue efforts: “Part of my Lab research has been studying using ultra wide-band impulse radar for medical applications to diagnose injuries in austere environments, such as the mountains.”

For the past three years, he has served as a Livermore Emergency Duty Officer (LEDO), helping to direct the Lab’s response to emergencies or problems, such as electrical outages, chemical spills or grassland fires at Site 300.

“It’s been an awesome job. The reason I like it is because it allows us to help the emergency response community and it helps me to appreciate the breadth and depth of the resources the Lab has in protecting our community,” he said.

Looking back on his time with BAMRU and the Upper Valley Wilderness Response Team, Chang says: “One of the deepest impressions that I’ve come to from my years doing search-and-rescue missions is the preciousness of people’s lives.”

Even after he retires from the Lab some time years into the future, Chang hopes he can continue to be involved in search-and-rescue work.

“Having worked on search-and-rescue missions for more than 25 years, it’s something that’s become a part of me and even a little bit of my identity.” And it’s also something that’s been good for many other people, too.